#MereExposureEffect

Do Not Read This Article! An Exploration of the Streisand Effect and Other Phenomena

27 December 2024

BY SCOTT M. GRAFFIUS | ScottGraffius.com

If there are any supplements or updates to this article after the date of publication, they will appear in the Post-Publication Notes section at the end of this article.

Introduction

In the grand carnival of human behavior and information flow, there are quirks and curiosities so odd yet impactful that they deserve a closer look. Among these is the Streisand Effect, a phenomenon so emblematic of unintended consequences that it practically shouts, "Whatever you do, don't think of a pink elephant!" Naturally, you imagine a pink elephant. This article takes you on a tour of the Streisand Effect and 20 other phenomena that shape how we perceive, act, and interact in our hyper-connected world.

Streisand Effect

The Streisand Effect is a paragon of irony where the very act of trying to bury information catapults it to stardom. Named after Barbra Streisand’s 2003 attempt to suppress an aerial photograph of her Malibu estate, the story plays out like a tragicomedy of psychological reactance. Initially viewed a few times, the image rocketed to over 420,000 views within a month of her lawsuit.

This effect thrives on one core principle: forbidden fruit tastes sweeter. Tell people they can’t see something, and their curiosity will spike faster than shares of a tech company during a bubble. Here’s the typical trajectory:

Some clever brands have sidestepped this pitfall with style. Netflix turned a copyright skirmish into a PR masterstroke, sending a witty cease-and-desist letter to a bar exploiting its Stranger Things branding. Similarly, a fast-food chain rebranded an infringing sandwich "Chicken Cease and Desist," spinning a potential crisis into marketing gold.

20 More Fascinating Phenomena

Let’s explore a veritable cabinet of curiosities—an assortment of quirks that reveal the magnificent irrationality and complexity of human behavior. For each of the 20 phenomena, there’s a short description followed by an elaboration.

Baader-Meinhof Phenomenon

The Baader-Meinhof Phenomenon: Spot a concept for the first time, and suddenly, it’s everywhere. It isn’t reality shifting; it’s your brain tuning its antenna.

Also known as the Frequency Illusion, it describes the experience where once you notice something for the first time, you see it everywhere. This isn't because the frequency of the occurrence has suddenly increased; rather, your brain has become selectively attuned to that particular stimulus. After initial exposure, your mind starts to pick up on things you might have previously overlooked or filtered out. This phenomenon is linked to selective attention, where your cognitive system prioritizes information that matches what was recently learned or focused on. Hence, it's not that reality has changed, but your perception has been altered to highlight what was once background noise. This can apply to anything from words, names, or ideas, making it seem like the world is suddenly saturated with these elements.

Barnum Effect

The Barnum Effect: We eagerly believe vague statements.

It was named after the showman P.T. Barnum, who was known for his ability to appeal to a broad audience with vague but seemingly personal statements. It involves the tendency for people to accept general or ambiguous personality descriptions as uniquely applicable to themselves. In 1948, psychologist Bertram Forer demonstrated in an experiment where students rated a generic personality sketch—believing it was tailored to them individually—as highly accurate. This effect is commonly seen in horoscopes, fortune-telling, and some forms of personality testing where broad statements are perceived as highly personal. It reveals much about human psychology, particularly our desire for uniqueness and validation, and it underscores the importance of skepticism toward generalized feedback. It’s also known as the Forer Effect.

Butterfly Effect

The Butterfly Effect: In the chaotic dance of the cosmos, a butterfly flaps its wings in Brazil, and Texas hosts a tornado. Tiny changes can result in monumental consequences.

This phenomenon originated from meteorologist Edward Lorenz's work in on chaos theory. It suggests that tiny changes in initial conditions can lead to infinitely different outcomes in complex systems. An example often cited is the metaphorical butterfly flapping its wings in Brazil, potentially setting off a tornado in Texas. This concept transcends meteorology. It also applies to economics and human behavior, showing how small actions can have grand impacts over time.

Bystander Effect

The Bystander Effect: A paradox of presence—more witnesses mean less action. Everyone assumes someone else will help, and often, no one does.

This psychological phenomenon explains that the likelihood of someone offering help decreases as the number of bystanders increases, due to diffusion of responsibility. Each person thinks someone else will act.

Cognitive Dissonance

Cognitive Dissonance: When beliefs and reality collide, the mental gymnastics commence. We’ll twist perceptions or rewrite beliefs to escape discomfort.

Cognitive dissonance occurs when one’s actions or new information contradicts beliefs or values, resulting in psychological discomfort. It's like an internal clash where the mind struggles to reconcile these discrepancies. To alleviate this tension, individuals might unconsciously change their attitudes, justify their behaviors, or ignore information that challenges their views. This mental gymnastics is essentially our brain's way of seeking harmony between our thoughts and actions. It's a common human experience, illustrating how we strive for internal consistency amidst the complexities of our beliefs and realities.

Confirmation Bias

Confirmation Bias: The Sherlock Holmes of selective thinking—seeking evidence to confirm our views while ignoring inconvenient truths.

This phenomenon was recognized by Peter Wason in the 1960s, although the concept has roots in earlier philosophical discussions. Confirmation bias leads individuals to favor information that confirms their pre-existing beliefs or values while downplaying or ignoring evidence that contradicts them. An everyday example is how people might selectively follow news sources that align with their political views, thus reinforcing their existing opinions. In scientific research, confirmation bias can skew hypothesis testing, leading to experiments designed to prove rather than disprove hypotheses. This bias has profound implications for decision-making processes, influencing everything from personal life choices to global policy decisions, often contributing to echo chambers and polarization.

Doppler Effect

The Doppler Effect: That ambulance siren’s pitch-shifting wail? A wave phenomenon that applies as much to physics as it does to our perception of life’s fleeting moments.

This was first described by Christian Doppler. It pertains to the change in wave frequency observed when the source and observer move relative to each other. This is commonly experienced when an ambulance siren sounds higher pitched as it approaches and lower as it moves away. The Doppler Effect applies not just to sound but also to light, which is crucial for astronomical observations like redshift, indicating an object is moving away from us. This phenomenon is also fundamental in radar, sonar, medical ultrasound imaging, and other technologies.

Dunning-Kruger Effect

The Dunning-Kruger Effect: A delightful irony: the less we know, the more we think we know. A few guitar chords, and we’re ready for a stadium tour.

David Dunning and Justin Kruger identified this effect. They demonstrated that people with lower abilities generally overestimate their competence. A classic example is someone who has just learned to play a few chords on a guitar thinking they're ready for a concert. This effect influences education, self-assessment in professional settings, and personal development, highlighting the need for metacognitive awareness.

Fundamental Attribution Error

Fundamental Attribution Error: Blame others’ behavior on their character, not their circumstances. Yet, when it’s us, the reverse applies. Empathy, thy name is elusive.

Named by Lee Ross, this phenomenon refers to the tendency to attribute others' actions to their inherent character rather than external situations. For example, if someone fails to return a greeting, we might call them rude—not considering they might have been distracted or in a bad mood. This bias significantly affects how we judge others' behaviors in daily life, legal contexts, and interpersonal relationships, often leading to misinterpretations of motives. Recognizing this error can lead to more empathetic and accurate social interactions, as it encourages us to consider situational factors that might influence behavior.

Groupthink

Groupthink: Harmony at the expense of sanity. Decisions made in unison can lead to spectacular failures, all in the name of avoiding dissent.

Within a group, the desire for harmony or conformity can lead to irrational or poor decision-making, where dissenting opinions are suppressed, and alternatives are not considered. Here’s an example: A company's board agrees to a risky venture without critique, leading to a failed project, due to everyone echoing the CEO's optimism.

Halo Effect

The Halo Effect: Charm, beauty, or charisma often masks flaws, convincing us the golden glow is based on true merit.

First identified by Edward Thorndike, the Halo Effect describes the cognitive bias where our overall impression of a person influences our perception of their character or abilities. An example is when an attractive individual is assumed to be more intelligent, kind, or competent without direct evidence. This effect can skew judgments in various contexts, such as in employment where a candidate's attractiveness or charm might overshadow their actual qualifications. It's prevalent in media and politics, where a leader's charisma can lead to positive evaluations across all aspects of their performance, highlighting how superficial traits can color our assessments of others.

Hawthorne Effect

The Hawthorne Effect: The mere act of being observed can boost performance—proof that attention is a powerful motivator.

Named after studies conducted at the Hawthorne Works of Western Electric, this effect shows how workers' productivity increases when they feel observed and valued. For instance, during these studies, workers' output increased when lighting was changed or when they were given more attention. This phenomenon has implications for workplace motivation, management practices, and research methodology, emphasizing the importance of human factors in organizational behavior.

Mandela Effect

The Mandela Effect: Did Nelson Mandela die in prison in the 1980s? No. But if you thought so, you’re in good company—a testament to the fallibility of collective memory.

Coined by Fiona Broome in 2009, the Mandela Effect describes a phenomenon where many people share the same false memory, such as the belief that Nelson Mandela died in prison in the 1980s rather than in 2013. Other examples include the misremembering of "Berenstain Bears" as "Berenstein Bears" and the mistaken belief that the Monopoly man sports a monocle (which he does not). The Mandela Effect prompts intriguing questions about how memory might be shaped by media and social interactions.

Mere Exposure Effect

The Mere Exposure Effect: Familiarity breeds affection, not contempt. Repeated exposure to an ad, song, or face, and suddenly, you’re a fan.

Robert Zajonc's research in the 1960s brought to light the Mere Exposure Effect, which posits that people often prefer things because they are familiar with them. For example, repeated exposure to a song or advertisement can increase one's liking towards it. This effect is widely used in marketing strategies, where brands aim to increase exposure to boost consumer preference. It also plays a role in social interactions, where familiarity can breed fondness, explaining why we might feel more comfortable around people we see often.

Observer Effect

The Observer Effect: In both physics and psychology, observation changes outcomes.

In quantum mechanics, this effect was highlighted by experiments like Werner Heisenberg's uncertainty principle in the early 20th century, where measuring a particle changes its state. A simple example is observing an electron that alters its position or momentum. Beyond physics, this term metaphorically applies to social sciences where the presence of an observer can influence the behavior of those being studied.

Placebo Effect

The Placebo Effect: Belief heals. Sugar pills—wielded by faith—can perform medical marvels.

This effect has been observed since ancient times but was scientifically recognized in the 20th century. It involves patients experiencing an improvement in symptoms after receiving a treatment with no therapeutic value, solely because they believe in its efficacy. For example, in clinical trials, placebo groups often report symptom relief. This effect underscores the power of the mind in healing, influencing medical ethics, drug testing protocols, and even shaping treatments like psychotherapy where belief in recovery can be therapeutic.

Pygmalion Effect

The Pygmalion Effect: High expectations can inspire greatness, proving that belief in potential often creates it.

Named after the myth of Pygmalion, this effect was highlighted in a 1968 study by Rosenthal and Jacobson, where teachers' expectations impacted student performance. If teachers were told certain students would excel, those students did indeed perform better, even if the "expectations" were randomly assigned. This phenomenon underscores the influence of expectations in education, leadership, and personal development, showing how belief can shape reality.

Self-Fulfilling Prophecy

Self-Fulfilling Prophecy: Expect failure, and you’ll unconsciously create it. Expect success, and the stars align in your favor.

This phenomenon is when expectations are manifested in reality. It's a cycle where belief influences outcome, which then confirms the belief. Here’s an example: A student expecting to fail an exam might not study, leading to the poor performance they anticipated.

Social Loafing

Social Loafing: In a group, effort dilutes. Individuals pull less weight, assuming others will pick up the slack.

In group settings, individuals might exert less effort than they would alone, believing their contribution is less noticeable or that others will compensate. This can lead to decreased productivity. Here’s an example: During a group project, one member does minimal work, assuming others will complete the task.

Zeigarnik Effect

The Zeigarnik Effect: Unfinished tasks linger in the mind like unresolved cliffhangers, demanding resolution and keeping us engaged.

This phenomenon was named after Bluma Zeigarnik, who observed waitstaff recalling orders better while they were still in progress. This effect explains why unfinished tasks tend to stick in our memory more than completed ones. For example, you might find yourself thinking about an unfinished project more than one you’ve completed. This phenomenon has significant implications for learning and productivity, suggesting that breaking tasks into segments can enhance memory retention and motivation to complete them. It's also why cliffhangers in narratives are compelling; they leave the audience with an unresolved tension that drives engagement.

Conclusion

Understanding these phenomena is not just an exercise in intellectual curiosity. It’s a toolkit for navigating life, spotting the irrational, and occasionally, turning it to your advantage. After all, in the chaos of human behavior, the unexpected often hides the greatest opportunity.

Read on to learn:

About Scott M. Graffius

Scott M. Graffius is an agile project management expert practitioner, consultant, award-winning author, and international public speaker.

Graffius has generated more than USD $1.9 billion in business value for organizations served, including Fortune 500 companies. Businesses and industries range from technology (including R&D and AI) to entertainment, financial services, and healthcare, government, social media, and more.

Graffius leads the professional services firm Exceptional PPM and PMO Solutions, along with its subsidiary Exceptional Agility. These consultancies offer strategic and tactical advisory, training, embedded talent, and consulting services to public, private, and government sectors. They help organizations enhance their capabilities and results in agile, project management, program management, portfolio management, and PMO leadership, supporting innovation and driving competitive advantage. The consultancies confidently back services with a Delighted Client Guarantee™. Graffius is a former vice president of project management with a publicly traded provider of diverse consumer products and services over the Internet. Before that, he ran and supervised the delivery of projects and programs in public and private organizations with businesses ranging from e-commerce to advanced technology products and services, retail, manufacturing, entertainment, and more. He has experience with consumer, business, reseller, government, and international markets.

He is the author of two award-winning books.

Organizations around the world invite Graffius to speak on tech (including AI), agile, project management, program management, portfolio management, and PMO leadership. He has developed and delivered unique and compelling talks and workshops. To date, Graffius has delivered 91 sessions across 25 countries. Select examples of events include Agile Trends Gov, BSides (Newcastle Upon Tyne), Conf42 Quantum Computing, DevDays Europe, DevOps Institute, DevOpsDays (Geneva), Frug’Agile, IEEE, Microsoft, Scottish Summit, Scrum Alliance RSG (Nepal), Techstars, and W Love Games International Video Game Development Conference (Helsinki), and more. With an average rating of 4.81 (on a scale of 1-5), his sessions are highly valued.

Prominent businesses, professional associations, government agencies, and universities have featured Graffius and his work including content from his books, talks, workshops, and more. Select examples include:

Graffius has been actively involved with the Project Management Institute (PMI) in the development of professional standards. He was a member of the team which produced the Practice Standard for Work Breakdown Structures—Second Edition. Graffius was a contributor and reviewer of A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge—Sixth Edition, The Standard for Program Management—Fourth Edition, and The Practice Standard for Project Estimating—Second Edition. He was also a subject matter expert reviewer of content for the PMI’s Congress. Beyond the PMI, Graffius also served as a member of the review team for two of the Scrum Alliance’s Global Scrum Gatherings.

Graffius has a bachelor’s degree in psychology with a focus in Human Factors. He holds eight professional certifications:

He is an active member of the Scrum Alliance, the Project Management Institute (PMI), and the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE).

He divides his time between Los Angeles and Paris, France.

About Agile Scrum: Your Quick Start Guide with Step-by-Step Instructions

Shifting customer needs are common in today's marketplace. Businesses must be adaptive and responsive to change while delivering an exceptional customer experience to be competitive.

There are a variety of frameworks supporting the development of products and services, and most approaches fall into one of two broad categories: traditional or agile. Traditional practices such as waterfall engage sequential development, while agile involves iterative and incremental deliverables. Organizations are increasingly embracing agile to manage projects, and best meet their business needs of rapid response to change, fast delivery speed, and more.

With clear and easy to follow step-by-step instructions, Scott M. Graffius's award-winning Agile Scrum: Your Quick Start Guide with Step-by-Step Instructions helps the reader:

Hailed by Literary Titan as “the book highlights the versatility of Scrum beautifully.”

Winner of 17 first place awards.

Agile Scrum: Your Quick Start Guide with Step-by-Step Instructions is available in paperback and ebook/Kindle in the United States and around the world. Some links by country follow.

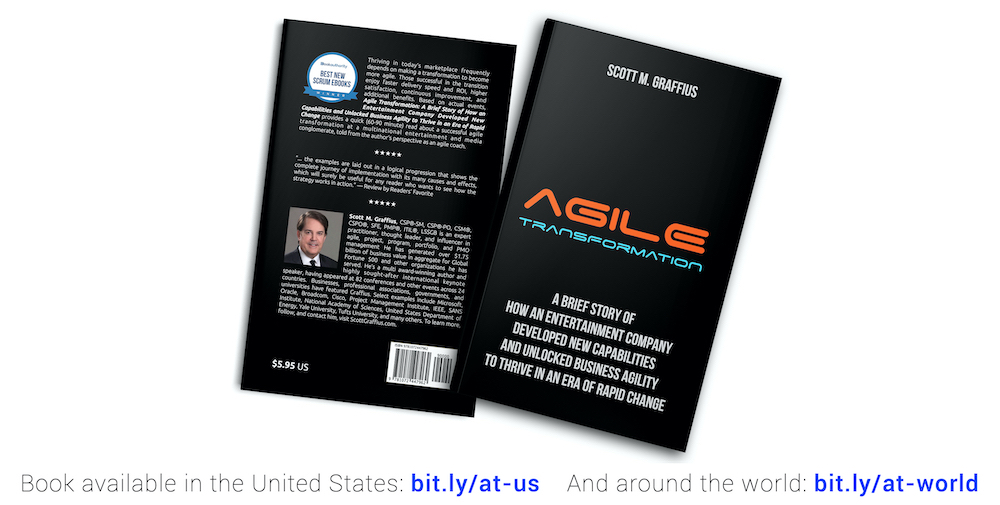

About Agile Transformation: A Brief Story of How an Entertainment Company Developed New Capabilities and Unlocked Business Agility to Thrive in an Era of Rapid Change

Thriving in today's marketplace frequently depends on making a transformation to become more agile. Those successful in the transition enjoy faster delivery speed and ROI, higher satisfaction, continuous improvement, and additional benefits.

Based on actual events, Agile Transformation: A Brief Story of How an Entertainment Company Developed New Capabilities and Unlocked Business Agility to Thrive in an Era of Rapid Change provides a quick (60-90 minute) read about a successful agile transformation at a multinational entertainment and media company, told from the author's perspective as an agile coach.

The award-winning book by Scott M. Graffius is available in paperback and ebook/Kindle in the United States and around the world. Some links by country follow.

References/Sources

How to Cite This Article

Graffius, Scott M. (2024, December 27). Do Not Read This Article! An Exploration of the Streisand Effect and Other Phenomena. Available at: https://scottgraffius.com/blog/files/streisand-effect.html. DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.2.30652.14726.

Post-Publication Notes

If there are any supplements or updates to this article after the date of publication, they will appear here.

Update on 22 January 2025

After reading this article, several people asked about how psychological effects are related to psychological operations (PsyOps). Based on that interest, here's an overview.

Psychological effects refer to the natural or induced changes in individual or collective behavior, emotions, or cognition due to psychological phenomena like cognitive biases, social influence, or stress responses. These effects can shape how people perceive and react to the world around them, often without explicit intent from external parties. On the other hand, psychological operations (PsyOps) are orchestrated and strategic efforts typically employed by military, governmental, or corporate entities to influence perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors of target audiences for specific objectives. While psychological effects occur organically or as a byproduct of various stimuli, PsyOps deliberately utilize these effects to achieve particular outcomes, like altering public opinion. The overlap comes into play when PsyOps leverage known psychological effects, such as the Streisand Effect or confirmation bias, to amplify their impact. This intersection highlights how understanding human psychology can be used both passively, in everyday interactions, and actively, as part of a calculated strategy.

Distilling it even further:

Update on 25 June 2025

An in-depth treatment of PsyOps was published here.

Short Link for Article

The short link for this article is https://bit.ly/psy-efx

Copyright

Copyright © Scott M. Graffius. All rights reserved.

Content on this site—including text, images, videos, and data—may not be used for training or input into any artificial intelligence, machine learning, or automatized learning systems, or published, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without the express written permission of Scott M. Graffius.

If there are any supplements or updates to this article after the date of publication, they will appear in the Post-Publication Notes section at the end of this article.

Introduction

In the grand carnival of human behavior and information flow, there are quirks and curiosities so odd yet impactful that they deserve a closer look. Among these is the Streisand Effect, a phenomenon so emblematic of unintended consequences that it practically shouts, "Whatever you do, don't think of a pink elephant!" Naturally, you imagine a pink elephant. This article takes you on a tour of the Streisand Effect and 20 other phenomena that shape how we perceive, act, and interact in our hyper-connected world.

Streisand Effect

The Streisand Effect is a paragon of irony where the very act of trying to bury information catapults it to stardom. Named after Barbra Streisand’s 2003 attempt to suppress an aerial photograph of her Malibu estate, the story plays out like a tragicomedy of psychological reactance. Initially viewed a few times, the image rocketed to over 420,000 views within a month of her lawsuit.

This effect thrives on one core principle: forbidden fruit tastes sweeter. Tell people they can’t see something, and their curiosity will spike faster than shares of a tech company during a bubble. Here’s the typical trajectory:

- A censorship attempt ignites interest.

- Public and media curiosity explodes.

- Social media and news amplify the intrigue.

- The original goal of suppression crumbles into a viral free-for-all.

Some clever brands have sidestepped this pitfall with style. Netflix turned a copyright skirmish into a PR masterstroke, sending a witty cease-and-desist letter to a bar exploiting its Stranger Things branding. Similarly, a fast-food chain rebranded an infringing sandwich "Chicken Cease and Desist," spinning a potential crisis into marketing gold.

20 More Fascinating Phenomena

Let’s explore a veritable cabinet of curiosities—an assortment of quirks that reveal the magnificent irrationality and complexity of human behavior. For each of the 20 phenomena, there’s a short description followed by an elaboration.

Baader-Meinhof Phenomenon

The Baader-Meinhof Phenomenon: Spot a concept for the first time, and suddenly, it’s everywhere. It isn’t reality shifting; it’s your brain tuning its antenna.

Also known as the Frequency Illusion, it describes the experience where once you notice something for the first time, you see it everywhere. This isn't because the frequency of the occurrence has suddenly increased; rather, your brain has become selectively attuned to that particular stimulus. After initial exposure, your mind starts to pick up on things you might have previously overlooked or filtered out. This phenomenon is linked to selective attention, where your cognitive system prioritizes information that matches what was recently learned or focused on. Hence, it's not that reality has changed, but your perception has been altered to highlight what was once background noise. This can apply to anything from words, names, or ideas, making it seem like the world is suddenly saturated with these elements.

Barnum Effect

The Barnum Effect: We eagerly believe vague statements.

It was named after the showman P.T. Barnum, who was known for his ability to appeal to a broad audience with vague but seemingly personal statements. It involves the tendency for people to accept general or ambiguous personality descriptions as uniquely applicable to themselves. In 1948, psychologist Bertram Forer demonstrated in an experiment where students rated a generic personality sketch—believing it was tailored to them individually—as highly accurate. This effect is commonly seen in horoscopes, fortune-telling, and some forms of personality testing where broad statements are perceived as highly personal. It reveals much about human psychology, particularly our desire for uniqueness and validation, and it underscores the importance of skepticism toward generalized feedback. It’s also known as the Forer Effect.

Butterfly Effect

The Butterfly Effect: In the chaotic dance of the cosmos, a butterfly flaps its wings in Brazil, and Texas hosts a tornado. Tiny changes can result in monumental consequences.

This phenomenon originated from meteorologist Edward Lorenz's work in on chaos theory. It suggests that tiny changes in initial conditions can lead to infinitely different outcomes in complex systems. An example often cited is the metaphorical butterfly flapping its wings in Brazil, potentially setting off a tornado in Texas. This concept transcends meteorology. It also applies to economics and human behavior, showing how small actions can have grand impacts over time.

Bystander Effect

The Bystander Effect: A paradox of presence—more witnesses mean less action. Everyone assumes someone else will help, and often, no one does.

This psychological phenomenon explains that the likelihood of someone offering help decreases as the number of bystanders increases, due to diffusion of responsibility. Each person thinks someone else will act.

Cognitive Dissonance

Cognitive Dissonance: When beliefs and reality collide, the mental gymnastics commence. We’ll twist perceptions or rewrite beliefs to escape discomfort.

Cognitive dissonance occurs when one’s actions or new information contradicts beliefs or values, resulting in psychological discomfort. It's like an internal clash where the mind struggles to reconcile these discrepancies. To alleviate this tension, individuals might unconsciously change their attitudes, justify their behaviors, or ignore information that challenges their views. This mental gymnastics is essentially our brain's way of seeking harmony between our thoughts and actions. It's a common human experience, illustrating how we strive for internal consistency amidst the complexities of our beliefs and realities.

Confirmation Bias

Confirmation Bias: The Sherlock Holmes of selective thinking—seeking evidence to confirm our views while ignoring inconvenient truths.

This phenomenon was recognized by Peter Wason in the 1960s, although the concept has roots in earlier philosophical discussions. Confirmation bias leads individuals to favor information that confirms their pre-existing beliefs or values while downplaying or ignoring evidence that contradicts them. An everyday example is how people might selectively follow news sources that align with their political views, thus reinforcing their existing opinions. In scientific research, confirmation bias can skew hypothesis testing, leading to experiments designed to prove rather than disprove hypotheses. This bias has profound implications for decision-making processes, influencing everything from personal life choices to global policy decisions, often contributing to echo chambers and polarization.

Doppler Effect

The Doppler Effect: That ambulance siren’s pitch-shifting wail? A wave phenomenon that applies as much to physics as it does to our perception of life’s fleeting moments.

This was first described by Christian Doppler. It pertains to the change in wave frequency observed when the source and observer move relative to each other. This is commonly experienced when an ambulance siren sounds higher pitched as it approaches and lower as it moves away. The Doppler Effect applies not just to sound but also to light, which is crucial for astronomical observations like redshift, indicating an object is moving away from us. This phenomenon is also fundamental in radar, sonar, medical ultrasound imaging, and other technologies.

Dunning-Kruger Effect

The Dunning-Kruger Effect: A delightful irony: the less we know, the more we think we know. A few guitar chords, and we’re ready for a stadium tour.

David Dunning and Justin Kruger identified this effect. They demonstrated that people with lower abilities generally overestimate their competence. A classic example is someone who has just learned to play a few chords on a guitar thinking they're ready for a concert. This effect influences education, self-assessment in professional settings, and personal development, highlighting the need for metacognitive awareness.

Fundamental Attribution Error

Fundamental Attribution Error: Blame others’ behavior on their character, not their circumstances. Yet, when it’s us, the reverse applies. Empathy, thy name is elusive.

Named by Lee Ross, this phenomenon refers to the tendency to attribute others' actions to their inherent character rather than external situations. For example, if someone fails to return a greeting, we might call them rude—not considering they might have been distracted or in a bad mood. This bias significantly affects how we judge others' behaviors in daily life, legal contexts, and interpersonal relationships, often leading to misinterpretations of motives. Recognizing this error can lead to more empathetic and accurate social interactions, as it encourages us to consider situational factors that might influence behavior.

Groupthink

Groupthink: Harmony at the expense of sanity. Decisions made in unison can lead to spectacular failures, all in the name of avoiding dissent.

Within a group, the desire for harmony or conformity can lead to irrational or poor decision-making, where dissenting opinions are suppressed, and alternatives are not considered. Here’s an example: A company's board agrees to a risky venture without critique, leading to a failed project, due to everyone echoing the CEO's optimism.

Halo Effect

The Halo Effect: Charm, beauty, or charisma often masks flaws, convincing us the golden glow is based on true merit.

First identified by Edward Thorndike, the Halo Effect describes the cognitive bias where our overall impression of a person influences our perception of their character or abilities. An example is when an attractive individual is assumed to be more intelligent, kind, or competent without direct evidence. This effect can skew judgments in various contexts, such as in employment where a candidate's attractiveness or charm might overshadow their actual qualifications. It's prevalent in media and politics, where a leader's charisma can lead to positive evaluations across all aspects of their performance, highlighting how superficial traits can color our assessments of others.

Hawthorne Effect

The Hawthorne Effect: The mere act of being observed can boost performance—proof that attention is a powerful motivator.

Named after studies conducted at the Hawthorne Works of Western Electric, this effect shows how workers' productivity increases when they feel observed and valued. For instance, during these studies, workers' output increased when lighting was changed or when they were given more attention. This phenomenon has implications for workplace motivation, management practices, and research methodology, emphasizing the importance of human factors in organizational behavior.

Mandela Effect

The Mandela Effect: Did Nelson Mandela die in prison in the 1980s? No. But if you thought so, you’re in good company—a testament to the fallibility of collective memory.

Coined by Fiona Broome in 2009, the Mandela Effect describes a phenomenon where many people share the same false memory, such as the belief that Nelson Mandela died in prison in the 1980s rather than in 2013. Other examples include the misremembering of "Berenstain Bears" as "Berenstein Bears" and the mistaken belief that the Monopoly man sports a monocle (which he does not). The Mandela Effect prompts intriguing questions about how memory might be shaped by media and social interactions.

Mere Exposure Effect

The Mere Exposure Effect: Familiarity breeds affection, not contempt. Repeated exposure to an ad, song, or face, and suddenly, you’re a fan.

Robert Zajonc's research in the 1960s brought to light the Mere Exposure Effect, which posits that people often prefer things because they are familiar with them. For example, repeated exposure to a song or advertisement can increase one's liking towards it. This effect is widely used in marketing strategies, where brands aim to increase exposure to boost consumer preference. It also plays a role in social interactions, where familiarity can breed fondness, explaining why we might feel more comfortable around people we see often.

Observer Effect

The Observer Effect: In both physics and psychology, observation changes outcomes.

In quantum mechanics, this effect was highlighted by experiments like Werner Heisenberg's uncertainty principle in the early 20th century, where measuring a particle changes its state. A simple example is observing an electron that alters its position or momentum. Beyond physics, this term metaphorically applies to social sciences where the presence of an observer can influence the behavior of those being studied.

Placebo Effect

The Placebo Effect: Belief heals. Sugar pills—wielded by faith—can perform medical marvels.

This effect has been observed since ancient times but was scientifically recognized in the 20th century. It involves patients experiencing an improvement in symptoms after receiving a treatment with no therapeutic value, solely because they believe in its efficacy. For example, in clinical trials, placebo groups often report symptom relief. This effect underscores the power of the mind in healing, influencing medical ethics, drug testing protocols, and even shaping treatments like psychotherapy where belief in recovery can be therapeutic.

Pygmalion Effect

The Pygmalion Effect: High expectations can inspire greatness, proving that belief in potential often creates it.

Named after the myth of Pygmalion, this effect was highlighted in a 1968 study by Rosenthal and Jacobson, where teachers' expectations impacted student performance. If teachers were told certain students would excel, those students did indeed perform better, even if the "expectations" were randomly assigned. This phenomenon underscores the influence of expectations in education, leadership, and personal development, showing how belief can shape reality.

Self-Fulfilling Prophecy

Self-Fulfilling Prophecy: Expect failure, and you’ll unconsciously create it. Expect success, and the stars align in your favor.

This phenomenon is when expectations are manifested in reality. It's a cycle where belief influences outcome, which then confirms the belief. Here’s an example: A student expecting to fail an exam might not study, leading to the poor performance they anticipated.

Social Loafing

Social Loafing: In a group, effort dilutes. Individuals pull less weight, assuming others will pick up the slack.

In group settings, individuals might exert less effort than they would alone, believing their contribution is less noticeable or that others will compensate. This can lead to decreased productivity. Here’s an example: During a group project, one member does minimal work, assuming others will complete the task.

Zeigarnik Effect

The Zeigarnik Effect: Unfinished tasks linger in the mind like unresolved cliffhangers, demanding resolution and keeping us engaged.

This phenomenon was named after Bluma Zeigarnik, who observed waitstaff recalling orders better while they were still in progress. This effect explains why unfinished tasks tend to stick in our memory more than completed ones. For example, you might find yourself thinking about an unfinished project more than one you’ve completed. This phenomenon has significant implications for learning and productivity, suggesting that breaking tasks into segments can enhance memory retention and motivation to complete them. It's also why cliffhangers in narratives are compelling; they leave the audience with an unresolved tension that drives engagement.

Conclusion

Understanding these phenomena is not just an exercise in intellectual curiosity. It’s a toolkit for navigating life, spotting the irrational, and occasionally, turning it to your advantage. After all, in the chaos of human behavior, the unexpected often hides the greatest opportunity.

Read on to learn:

- About Scott M. Graffius,

- References/Sources,

- How to Cite This Article,

- and more.

About Scott M. Graffius

Scott M. Graffius is an agile project management expert practitioner, consultant, award-winning author, and international public speaker.

Graffius has generated more than USD $1.9 billion in business value for organizations served, including Fortune 500 companies. Businesses and industries range from technology (including R&D and AI) to entertainment, financial services, and healthcare, government, social media, and more.

Graffius leads the professional services firm Exceptional PPM and PMO Solutions, along with its subsidiary Exceptional Agility. These consultancies offer strategic and tactical advisory, training, embedded talent, and consulting services to public, private, and government sectors. They help organizations enhance their capabilities and results in agile, project management, program management, portfolio management, and PMO leadership, supporting innovation and driving competitive advantage. The consultancies confidently back services with a Delighted Client Guarantee™. Graffius is a former vice president of project management with a publicly traded provider of diverse consumer products and services over the Internet. Before that, he ran and supervised the delivery of projects and programs in public and private organizations with businesses ranging from e-commerce to advanced technology products and services, retail, manufacturing, entertainment, and more. He has experience with consumer, business, reseller, government, and international markets.

He is the author of two award-winning books.

- His first book, Agile Scrum: Your Quick Start Guide with Step-by-Step Instructions (ISBN-13: 9781533370242), received 17 awards.

- His second book is Agile Transformation: A Brief Story of How an Entertainment Company Developed New Capabilities and Unlocked Business Agility to Thrive in an Era of Rapid Change (ISBN-13: 9781072447962). BookAuthority named it one of the best Scrum books of all time.

Organizations around the world invite Graffius to speak on tech (including AI), agile, project management, program management, portfolio management, and PMO leadership. He has developed and delivered unique and compelling talks and workshops. To date, Graffius has delivered 91 sessions across 25 countries. Select examples of events include Agile Trends Gov, BSides (Newcastle Upon Tyne), Conf42 Quantum Computing, DevDays Europe, DevOps Institute, DevOpsDays (Geneva), Frug’Agile, IEEE, Microsoft, Scottish Summit, Scrum Alliance RSG (Nepal), Techstars, and W Love Games International Video Game Development Conference (Helsinki), and more. With an average rating of 4.81 (on a scale of 1-5), his sessions are highly valued.

Prominent businesses, professional associations, government agencies, and universities have featured Graffius and his work including content from his books, talks, workshops, and more. Select examples include:

- Adobe,

- American Management Association,

- Amsterdam Public Health Research Institute,

- Bayer,

- Boston University,

- Broadcom,

- Cisco,

- Constructor University Germany,

- Deimos Aerospace,

- DevOps Institute,

- EU's European Commission,

- Ford Motor Company,

- Hasso Plattner Institute Germany,

- IEEE,

- Johns Hopkins University,

- London South Bank University,

- Microsoft,

- National Academy of Sciences,

- New Zealand Government,

- Oracle,

- Pinterest Inc.,

- Project Management Institute,

- TBS Switzerland,

- Torrens University Australia,

- Tufts University,

- UC San Diego,

- UK Sports Institute,

- University of Galway Ireland,

- U.S. Department of Energy,

- U.S. National Park Service,

- U.S. Tennis Association,

- Virginia Tech,

- Warsaw University of Technology,

- Yale University,

- and many others.

Graffius has been actively involved with the Project Management Institute (PMI) in the development of professional standards. He was a member of the team which produced the Practice Standard for Work Breakdown Structures—Second Edition. Graffius was a contributor and reviewer of A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge—Sixth Edition, The Standard for Program Management—Fourth Edition, and The Practice Standard for Project Estimating—Second Edition. He was also a subject matter expert reviewer of content for the PMI’s Congress. Beyond the PMI, Graffius also served as a member of the review team for two of the Scrum Alliance’s Global Scrum Gatherings.

Graffius has a bachelor’s degree in psychology with a focus in Human Factors. He holds eight professional certifications:

- Certified SAFe 6 Agilist (SA),

- Certified Scrum Professional - ScrumMaster (CSP-SM),

- Certified Scrum Professional - Product Owner (CSP-PO),

- Certified ScrumMaster (CSM),

- Certified Scrum Product Owner (CSPO),

- Project Management Professional (PMP),

- Lean Six Sigma Green Belt (LSSGB), and

- IT Service Management Foundation (ITIL).

He is an active member of the Scrum Alliance, the Project Management Institute (PMI), and the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE).

He divides his time between Los Angeles and Paris, France.

About Agile Scrum: Your Quick Start Guide with Step-by-Step Instructions

Shifting customer needs are common in today's marketplace. Businesses must be adaptive and responsive to change while delivering an exceptional customer experience to be competitive.

There are a variety of frameworks supporting the development of products and services, and most approaches fall into one of two broad categories: traditional or agile. Traditional practices such as waterfall engage sequential development, while agile involves iterative and incremental deliverables. Organizations are increasingly embracing agile to manage projects, and best meet their business needs of rapid response to change, fast delivery speed, and more.

With clear and easy to follow step-by-step instructions, Scott M. Graffius's award-winning Agile Scrum: Your Quick Start Guide with Step-by-Step Instructions helps the reader:

- Implement and use the most popular agile framework―Scrum;

- Deliver products in short cycles with rapid adaptation to change, fast time-to-market, and continuous improvement; and

- Support innovation and drive competitive advantage.

Hailed by Literary Titan as “the book highlights the versatility of Scrum beautifully.”

Winner of 17 first place awards.

Agile Scrum: Your Quick Start Guide with Step-by-Step Instructions is available in paperback and ebook/Kindle in the United States and around the world. Some links by country follow.

- 🇧🇷 Brazil

- 🇨🇦 Canada

- 🇨🇿 Czech Republic

- 🇩🇰 Denmark

- 🇫🇮 Finland

- 🇫🇷 France

- 🇩🇪 Germany

- 🇬🇷 Greece

- 🇭🇺 Hungary

- 🇮🇳 India

- 🇮🇪 Ireland

- 🇮🇱 Israel

- 🇮🇹 Italy

- 🇯🇵 Japan

- 🇱🇺 Luxembourg

- 🇲🇽 Mexico

- 🇳🇱 Netherlands

- 🇳🇿 New Zealand

- 🇳🇴 Norway

- 🇪🇸 Spain

- 🇸🇪 Sweden

- 🇨🇭 Switzerland

- 🇦🇪 UAE

- 🇬🇧 United Kingdom

- 🇺🇸 United States

About Agile Transformation: A Brief Story of How an Entertainment Company Developed New Capabilities and Unlocked Business Agility to Thrive in an Era of Rapid Change

Thriving in today's marketplace frequently depends on making a transformation to become more agile. Those successful in the transition enjoy faster delivery speed and ROI, higher satisfaction, continuous improvement, and additional benefits.

Based on actual events, Agile Transformation: A Brief Story of How an Entertainment Company Developed New Capabilities and Unlocked Business Agility to Thrive in an Era of Rapid Change provides a quick (60-90 minute) read about a successful agile transformation at a multinational entertainment and media company, told from the author's perspective as an agile coach.

The award-winning book by Scott M. Graffius is available in paperback and ebook/Kindle in the United States and around the world. Some links by country follow.

- 🇦🇺 Australia

- 🇦🇹 Austria

- 🇧🇷 Brazil

- 🇨🇦 Canada

- 🇨🇿 Czech Republic

- 🇩🇰 Denmark

- 🇫🇮 Finland

- 🇫🇷 France

- 🇩🇪 Germany

- 🇬🇷 Greece

- 🇮🇳 India

- 🇮🇪 Ireland

- 🇯🇵 Japan

- 🇱🇺 Luxembourg

- 🇲🇽 Mexico

- 🇳🇱 Netherlands

- 🇳🇿 New Zealand

- 🇪🇸 Spain

- 🇸🇪 Sweden

- 🇨🇭 Switzerland

- 🇦🇪 United Arab Emirates

- 🇬🇧 United Kingdom

- 🇺🇸 United States

References/Sources

- Ackerman P. (2014). Nonsense, Common Sense, and Science of Expert Performance: Talent and Individual Differences. Intelligence, 45: 6–17.

- Bandura, A. (1977). Self-Efficacy: Toward a Unifying Theory of Behavioral Change. Psychological Review, 84 (2): 191-215.

- Beecher, H. K. (1955, December). The powerful placebo. Journal of the American Medical Association, 159 (17), 1602-1606.

- Bem, D. J. (1972). Self-perception theory. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 6: 1-62.

- Bruner, J. S., & Goodman, C. C. (1947). Value and Need as Organizing Factors in Perception. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 42 (1): 33-44.

- Cialdini, R. B. (1984). Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion. New York, New York: William Morrow and Company.

- Darley, J. M., & Latané, B. (1968). Bystander Intervention in Emergencies: Diffusion of Responsibility. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 8 (4), 377-383.

- Dickson, D. H.; and Kelly, I. W. (1985). The 'Barnum Effect' in Personality Assessment: A Review of the Literature. Psychological Reports, 57 (1): 367–382.

- Dweck, C. S. (1986). Motivational Processes Affecting Learning. American Psychologist, 41 (10): 1040-1048.

- Festinger, L. (1957). A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press.

- Forer, B. R. (1949). The Fallacy of Personal Validation: A Classroom Demonstration of Gullibility. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 44 (1): 118-123.

- Graffius, Scott M. (2024, January 22). Should You Be Nasty or Nice in Negotiations? Available at: https://scottgraffius.com/blog/files/win-win.html.

- Graffius, Scott M. (2024, January 5). Scott M. Graffius’ Phases of Team Development: 2024 Update. Available at: https://scottgraffius.com/blog/files/teams-2024.html. DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.2.28629.40168.

- Granick, J. (2012). Damage Control. Index on Censorship, 41 (4): 25-32.

- Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision Under Risk. Econometrica, 47 (2), 263-291.

- Kruger, J., & Dunning, D. (1999). Unskilled and Unaware of It: How Difficulties in Recognizing One's Own Incompetence Lead to Inflated Self-Assessments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77 (6): 1121-1134.

- Kuhn T. (1962). The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Latané, B., Williams, K., & Harkins, S. (1979). Many Hands Make Light the Work: The Causes and Consequences of Social Loafing. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37 (6): 822-832.

- Lorenz, E. N. (1963). Deterministic Nonperiodic Flow. Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences, 20 (2): 130-141.

- Maslow, A. H. (1943). A Theory of Human Motivation. Psychological Review, 50 (4): 370-396.

- Merton, R. K. (1948). The Self-Fulfilling Prophecy. The Antioch Review, 8 (2): 193-210.

- Milgram, S. (1963). Behavioral Study of Obedience. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 67 (4): 371-378.

- Precious, G. (2024, December 1). Drake's UMG Lawsuit Backfires as Kendrick Lamar's 'Not Like Us' Sees 440% Sales Surge and 20% Stream Increase. Baller Alert.

- Rosenthal, R., & Jacobson, L. (1968). Pygmalion in the Classroom. The Urban Review, 3 (1): 16-20.

- Ross, L. (1977). The Intuitive Psychologist and His Shortcomings: Distortions in the Attribution Process. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 10: 173-220.

- Siegel, R. (2008, February 29). 'The Streisand Effect' Snags Effort to Hide Documents. All Things Considered. NPR.

- Sinaceur, M., Adam, H., Van Kleef, G. & Galinsky, A. (2013, May 1). The Advantages of Being Unpredictable: How Emotional Inconsistency Extracts Concessions in Negotiation. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 49: 498-508.

- Sjöberg, L. (1982). Common Sense and Psychological Phenomena: A Reply to Smedslund. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 23: 83-85.

- Sjöberg, L. (1982). Logical Versus Psychological Necessity: A Discussion of the Role of Common Sense in Psychological Theory. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 23: 65–78.

- Steele-Johnson, D.; Beauregard, R. S.; Hoover, P. B.; and Schmidt, A. M. (2000). Goal Orientation and Task Demand Effects on Motivation, Affect, and Performance. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 85 (5): 724–738.

- Streisand, B. v. Adelman, K., No. SC 077 257 (Cal. Super. Ct. Dec. 31, 2003).

- Thorndike, E. L. (1920). A Constant Error in Psychological Ratings. Journal of Applied Psychology, 4 (1): 25-29.

- Tobacyk, Jerome; Milford, Gary; Springer, Thomas; and Tobacyk, Zofia (2010, June 10). Paranormal Beliefs and the Barnum Effect. Journal of Personality Assessment, 52 (4): 737–739.

- Wason, P. C. (1960). On the Failure to Eliminate Hypotheses in a Conceptual Task. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 12 (3): 129-140.

- Zajonc, R. B. (1968). Attitudinal Effects of Mere Exposure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 9 (2, Part 2): 1-27.

- Zimbardo, P. G. (1973). On the Ethics of Intervention in Human Psychological Research: With Special Reference to the Stanford Prison Experiment. Cognition, 2 (2): 243-256.

How to Cite This Article

Graffius, Scott M. (2024, December 27). Do Not Read This Article! An Exploration of the Streisand Effect and Other Phenomena. Available at: https://scottgraffius.com/blog/files/streisand-effect.html. DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.2.30652.14726.

Post-Publication Notes

If there are any supplements or updates to this article after the date of publication, they will appear here.

Update on 22 January 2025

After reading this article, several people asked about how psychological effects are related to psychological operations (PsyOps). Based on that interest, here's an overview.

Psychological effects refer to the natural or induced changes in individual or collective behavior, emotions, or cognition due to psychological phenomena like cognitive biases, social influence, or stress responses. These effects can shape how people perceive and react to the world around them, often without explicit intent from external parties. On the other hand, psychological operations (PsyOps) are orchestrated and strategic efforts typically employed by military, governmental, or corporate entities to influence perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors of target audiences for specific objectives. While psychological effects occur organically or as a byproduct of various stimuli, PsyOps deliberately utilize these effects to achieve particular outcomes, like altering public opinion. The overlap comes into play when PsyOps leverage known psychological effects, such as the Streisand Effect or confirmation bias, to amplify their impact. This intersection highlights how understanding human psychology can be used both passively, in everyday interactions, and actively, as part of a calculated strategy.

Distilling it even further:

- Psych Effects: Unexpected outcomes occur naturally, like the Streisand Effect, where attempts to conceal information backfires and inadvertently increases attention.

- PsyOps: Strategic, planned tactics by orgs to shape perception and influence behavior.

Update on 25 June 2025

An in-depth treatment of PsyOps was published here.

Short Link for Article

The short link for this article is https://bit.ly/psy-efx

Copyright

Copyright © Scott M. Graffius. All rights reserved.

Content on this site—including text, images, videos, and data—may not be used for training or input into any artificial intelligence, machine learning, or automatized learning systems, or published, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without the express written permission of Scott M. Graffius.